The near impossibility of getting any sleep in my tent during the Memorial Day weekend music festival helped me appreciate my conventional house and its dusty bedroom. My state of mind at around 3 am both nights at the festival was bizarre. At that hour, music was still heard intermittently in the campsite area, followed by whoops and hollers of drunken delight. It was all very benign, but still, it forced me to go into meditation mode, discounting all worldly phenomena. Such mental “nothing is real” efforts tend to carry over into the next few days, when things are back to “normal,” and should be considered “real.” So I am not sure what the benefits of another such “vacation” would be, except that the music was very enjoyable. I am considering doing it again next year but bringing my earplugs and getting there early enough to secure a less public campsite. Seeing people’s feet shuffle along six inches from the tent opening was disconcerting. It made me think about homeless people who live on the street in cardboard boxes. My husband, who joined me for the second night in the tent, commented that in fact, it did not resemble the experience of the homeless, because we could look forward to getting back to our conventional house and its dusty bedroom. A homeless person, by definition, could not do that, but would be in a continual state of insecurity and anxiety about their own welfare. Perhaps he’s right.

Everything is so impermanent: our houses and cars, our clothes, our jobs and their technologies, the things we think we are interested in, the fluctuating states of our health. I always revert to being a “big picture” person, maybe because I’m lazy. But most involvements, intellectual, personal, or artistic, seem sort of illusory to me. Or they do now that I’m older than I ever thought I would be.

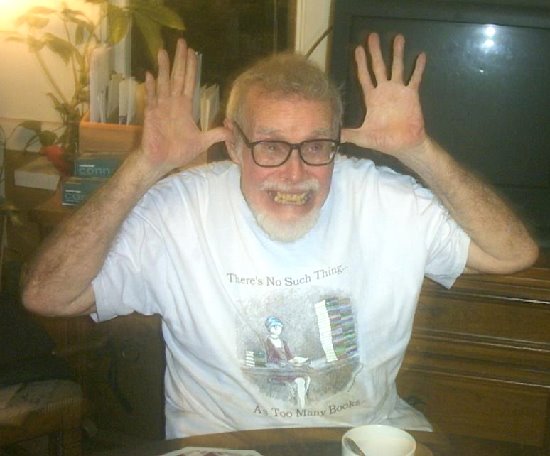

There is no reason to post the picture you see here except that it’s a “scene” that's now gone: my 19-year-old self, with my little brother (the Incredulous Pithecanthrope whose link is at left) during one of my infrequent visits to my family’s big suburban house (long since sold to another, more “together” family). It was 1969, and I was in recovery from the excesses of urban hippiedom, wearing my other brother’s hand-me-down vests and shirts. This was probably a few months before I moved in with a boyfriend and began working for a well-known Cambridge movie theater that, surprise, no longer exists.

There is no reason to post the picture you see here except that it’s a “scene” that's now gone: my 19-year-old self, with my little brother (the Incredulous Pithecanthrope whose link is at left) during one of my infrequent visits to my family’s big suburban house (long since sold to another, more “together” family). It was 1969, and I was in recovery from the excesses of urban hippiedom, wearing my other brother’s hand-me-down vests and shirts. This was probably a few months before I moved in with a boyfriend and began working for a well-known Cambridge movie theater that, surprise, no longer exists. The idea of impermanence (a shibboleth of Buddhism) is useful when you’re squirming in discomfort with just a thin mat between you and hard ground and being frequently jolted awake by sudden loud sounds as if undergoing torture by sleep deprivation experts. But it’s an idea that also gets you thinking—too much.